2.- Monopoly: advantages and disadvantages.

J.A. Schumpeter have stressed the benefical role that monopoly profits can play in the process of economic development. Schumpeter place considerable emphasis on innovation and the ability of particular types of firms to achieve technical advances. In this context the profits that monopolistic firms earn provide funds that can be invested in research and development. Whereas perfectly competitive firms must be content with a normal return on invested capital, monopolies have “surplus” funds with which to undertake the risky process of research.

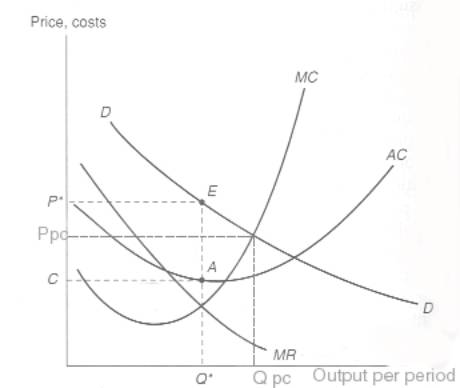

Monopoly Surplus

Monopoly price (P*)is higher than the perfect competition one (Ppc), and the output is smaller. That provides monopoly an surplus. This extra profits over the perfect competition will allow the monopolistic company invest in risky R&D.

More important, perhaps, the possibility of attaining a monopolistic position, or the desire to maintain such a position, provides an important incentive to keep one step ahead of potential competitors. Innovations in new products and cost-saving production techniques may be integrally related to the possibility of monopolization. Without such a monopolistic position, the full benefits of innovation could not be obtained by the innovating firm.

Schumpeter stresses the point that the monopolization of a market may make it less costly for a firm to plan its activities. Being the only source of supply for a product eliminates many of the contingencies that a firm in a competitive market must face. For example, a monopoly may not have to spend much on selling expenses (advertising, brand identification, visiting retailers, etc.) as would be the cas-e in a more competitive industry. Similarly, a monopoly may know more about the specific demand curve for its product and may more readily adapt to changing demand conditions.

Schumpeter rejected the anti-trust orthodoxy. He argued that the large firm operating in a concentrated market was the engine of technological progress; therefore, an industrial organization of large monopolistic firms offered decisive welfare advantages.

Schumpeter (1942) was primarily impressed by the qualitative differences between the innovative activities of small, entrepreneurial enterprises and those of large, modern corporations with formal R&D laboratories.

The empirical literature has interpreted Schumpeter’s claim for a large firm advantage in innovation as a proposition that innovative activity increases more proportionally than firm size does. Although some economist (Markham, 1965) have argued, however, that Schumpeter never claimed a continuous relationship between R&D and firm size, but only that innovation no longer depended upon that initiative and genius of independent entrepreneurs. Rather, R&D had come to be conducted largely by the professional laboratories of large, bureaucratic corporations, and these had come the principal source of innovation in modern capitalist societies.

Galbraith (1952) argued that large firm size confers and advantage in innovation. Several justifications for a positive effect of firm size on inventive activity have been offered, (only some of which were suggested by Schumpeter).

One claim is that capital market imperfections confer and advantage on large firms in securing finance for risky R&D projects because size is correlated with the availability and stability of internally generated funds. A second claim is that there are scale economies in the R&D function itself. Another is that the returns from R&D are higher where the innovator has a larger volume of sales over which the fixed costs of innovation can be spread. R&D is also alleged to be more productive in large firms as a result of complementarities between R&D and another nonmanufacturing activities (e.g. marketing and financial planning) that may be better developed within large firms. Finally, it is sometimes suggested that large, diversified firms provide economies of scope or reduce the risk associated with the prospective returns to innovation.

In the Schumpeter discussion of the effects of market power on innovation there are two distinct themes. First, Schumpeter recognized that firms required the expectation of some forms of transient market power to have the incentive to invest in R&D. This is, of course, the principle underlying patent law; it associates the incentive to invest with the expectation of ex-post market power. Second, Schumpeter argued that an ex-ante oligopolistic market structure and the possession of ex-ante market power also favoured innovation. An oligopolistic market structure made rival behaviour more stable and predictable, and thereby reduced the uncertainty associated with excessive rivalry that tended to undermine the incentive to invent. Implicitly assuming that capital markets are imperfect, which effectively are, he also suggested that the profits derived from the possession of ex-ante market power provided firms with the internal financial resources necessary to invest in innovative activity.

Not all economists agree with the Schumpeterian view; counter-arguments have also been suggested. As firms grow large, efficiency in R&D is undermined either though the loss of managerial control, or, alternatively, through excessive bureaucratic control which diverts the attention of the firm’s bench scientist and technologists.

Moreover, as firms grow large, the incentives of individual scientist and entrepreneurs may be blunted as either their ability to capture the benefits from their individual efforts dismisses or their creative impulses are frustrated by the conservatism characteristic of the hierarchies of large corporations2.

Empirical research on the relationship between firm size and innovation:

Based on National Science Foundation (NSF) data from the 1950s and early 1960s, the research established that the likelihood of a firm conducting R&D increases with firm size and approaches unity among the largest firms. There is some skepticism over the positive relationship between the likelihood of performing R&D and firm size. Since databases covered only formal R&D, and could overlook the efforts of the non-specialized personnel which tend to perform most of the R&D for small firms.

In their research for a “Schumpeterian” advantage to firm size, economists focused most of their attention on the continuous relationship between R&D and firm size. R&D was found to vary closely with form size within industries, with typically explaining over half of its variation.

Scherer (1965) observed a more subtle relationship, that inventive activity, whether measured by input (personnel) or output (patents), increased more than proportionally with size up to a threshold, whereupon the relationship become basically proportional.

Utilizing the Science Policy Research Unit’s innovation data and employment statistics published by the UK Business Statistics Office, Wyatt derived time series data on the ration, innovation share/employment share, for firms in four employment categories, and this analysis showed an increase over time I the relative innovative efficiency firms with employment between 500 and 999, and more market decrease of firms with employment between 1,000 and 9,999. And finally, a consistently greater than unit relative innovative efficiency of firms with employment greater than 10,000.

On the basis of these data, Wyatt concludes that the fact that SMEs maintained their share of British innovation more successfully than firms with employment between 500 and 10,000 reflects not only structural industrial shifts, but also changing patterns of innovative efficiency.

Other studies suggested that overall firm size do not affect R&D performance.

The earliest studies examining the R&D-size relationship that used samples spanning multiple industries concluded that R&D rose somewhat more than proportionately with firm size. But these studies included no controls for industry effects. Since differences in the size distribution of firms across industries may reflect industry-level differences in the technologies, opportunities, and economies in production, distribution and other factors, we would expect industry effects to be correlated with firm size. As a consequence, the omission of such industry effects will likely bias estimates of the effects of size on innovation3.

The studies based on individual industries and the studies pooling observation across industries are subject to several limitations.

First4, most of the samples used in the regression studies are non-random, and no a huge effort has been done to study the presence of the effects of sample selection bias. Many of the earlier firm-level studies confined attention to the 500 or 1,000 largest firms in the manufacturing sector, and firms that reported no R&D were typically excluded from the sample.

Second, the studies vary in the degree to which they control for the characteristics of firms (other than size), despite the demonstrated importance of firms effects in explaining R&D intensity, and the likely collienarity between them and firm size. The absence of controls form firm size characteristics highlights the related point that many of the studies that hypothesize a relationship between firm size and R&D do so by appealing to the influence of what are claimed to be firm characteristics correlated with size, such as cash flow, degree of diversification, complementary capabilities, economies of scale in the R&D function and the ability to spread R&D costs over output. Most of these studies have not directly examined whether the observed relationship between size and R&D is indeed due to the influence of any of these hypothesized factors.

Third, although most of the studies of the R&D-firm size relationship attempted to control for industry effects, it is not a simple matter to control properly for industry effects in a sample of firm-level data because most larger firms are aggregations of business units engaged in a variety of industries.

Some studies suggest that it is the size of the business unit (or its correlates) rather than the size of the firm as a whole (or its correlates) that accounts for the close relationship between firm size and R&D.

Agreements and disagreements with the Schumpeterian views.

Although there are some kind of consensus that R&D rises proportionately with firm size among R&D performers. This finding has been widely interpreted as indicating that, contrary to Schumpeter, large size offered no advantage in the conduct of R&D. However, it’s been argued, by Fisher and Temin (1973), that to the extend that Schumpeter’s hypothesis can be given a clear formulation, it must refer to a relationship between innovative output and firm size, not to a relationship between R&D (an innovative input) and firm size, which is the one most commonly tested in the literature.

Some studies suggest that the relationship may be somewhat U-shaped, with the very largest firms displaying relatively high R&D productivity as well as the SMEs (i.e. SPRU-Wyatt analysis, mentioned before. Nevertheless, several studies exploiting measures of innovative output reinforced the earlier consensus of no advantage to size.

The apparent decline in R&D productivity with firm size has been explained in a number of ways. Some have speculated that larger firms are less efficient innovators than smaller firms, or that this relationship reflects dismissing returns to R&D. Other explanation is sample selection bias; only the most successful small firms innovators tend to be included in the samples that have been examined. If a SME do not have formal R&D department, although could have an investment on these areas, it is not measurable, and only if successful we will concern about that expenditure. Either formal R&D for small firms can be systematically underestimated.

The empirical patterns relating R&D and innovation to firm size are that R&D increases monotonically and typically proportionally, with firm size among R&D performers within industries, the number of innovation tends to increase less than proportionately than firm size, and R&D productivity tends to decline with firm size.

But, how can this relationship (positive monotonic) be reconciled with the appent decline in R&D productivity with firm size5?

A possible answer is that returns to R&D increase with the level of output over which the fixed costs of innovation may be spread6, can explain the close positive monotonic relationship between R&D and firm size in general. This simple idea of R&D costs spreading can also reconcile the positive R&D-firm size relationship with declining R&D productivity in firm size relationship with declining R&D productivity in firm size. Costs spreading makes the returns to R&D increase with contemporaneous firm size as a consequence of two factors that condition R&D activity within most industries.

First, to reap the returns to their innovations, firms typically rely on appropriability mechanisms such as secrecy or first-mover advantages which require them to exploit their innovations through their own output. Second, firms expected their growth due to innovation to be limited by their existing size. Together these two conditions may suggests that the larger is a business unit’s output level at the time it conducts its R&D, the greater the future output over which the fixed costs of innovation (i.e. its R&D expenditures) can be spread. Consequently, larger business unit size yield a higher return per R&D expenditure which induces more R&D effort.

Although these ideas suggest that large firms have an advantage in R&D, we have to emphasize that this advantage is not due to size per se but arises from two common industry characteristics, namely the appropriability conditions that confine firms to exploit their innovations chiefly through their own output and limited firm growth due to innovation7. And that expected growth due to innovation tends to be limited by existing firm size.

Effects of market structure on innovation (some views)

Some Economists, have supported Schumpeter position that firms in concentrated markets can more easily appropriate the returns from inventive activity. Other have demonstrated , under the assumption of perfect ex-post appropriability, that a firm’s gains from innovation at the margin are larger in an industry that is competitive ex-ante than under monopoly conditions. Still others have argued that insulation from competitive pressures breeds bureaucratic inertia and discourages innovation.

Phillips8 (1966) propose that causality might run from innovation to market structure, rather than in the reverse direction. Although Schumpeter envisioned that the market power accruing from successful innovation would be transitory, eroding as competitors entered the field, Phillips argued that, to the extend that “success breeds success” concentrated industrial structure would tend to emerge as a consequence of past innovation.

The most robust finding from the empirical research relating R&D to firm size and market structure is that there is a close, positive relationship between size and R&D. In addition, innovative output appears to increase less relative to firm size, and R&D productivity appears to decline as a firm’s size increases. These relationships suggest that size has little effect on innovation and that larger firms have no advantage in the conduct of R&D, and perhaps even a disadvantage. However, more recent research suggests that the close positive relationship between firms size and R&D may in fact signal a “cost-spreading” advantage and an increased capacity to assume risk of R&D than larger firms. Even if there are advantages in R&D for large firms, it does not follow that an industry composed of larger firms is actually more innovative.

Some studies that examine the relationship between market concentration and R&D have found a positive relationship, while others have found evidence that concentration has a negative effect on R&D. Even some evidence has been found of a non-linear, “inverted-U” relationship between R&D intensity and concentration.

Anyway, in spite of the consensus that size has little effect on innovation, size does have important consequences on innovation:

Some advantages of large firms are:

- The spread of fixed cost of innovation.

- Economies of scale and scope in R&D.

- Capital market imperfections confer advantages to large firms in securing finance for risky R&D projects .

Whatever the results of regressions are, it is clear than a concentrated market, or even a monopoly, is going to have an strong effect on innovation, as it has effects over other parameters such as output, price, etc.

In the following chapter we are going to analyse an empirical of the relationship of monopoly and innovation, case, Microsoft.

2 Indeed, Schupeter speculated that these alter features of the bureaucratization of inventive activity could ultimately impide capitalist development.

3 Relationship between R&D firm sized: typically estimated cross-sectionally on samples restricted to R&D performers and specified in long-long, linearly or with R&D intensity (i.e. R&D effort divided by a measure of firm size, usually sales) as the dependent variable and a measure of firm size as a regressor.

4 Wesley Cohen “Empirical studies of Innovative Activity”

5 Assuming that this decline is not simply an artifact of sample selection or a bias.

6 Offered previously as one possible explanation for why R&D might rise more than proportionately than firm size.

7 Appropriability and growth conditions are two important industry characteristics, but it has been observed that large firms are more innovative in concentrated industries with high barriers to entry, while smaller firms are more innovative in less concentrated industries that are less mature.

8 See bibliography.

Author: Pau Klein's Marketing Online

next